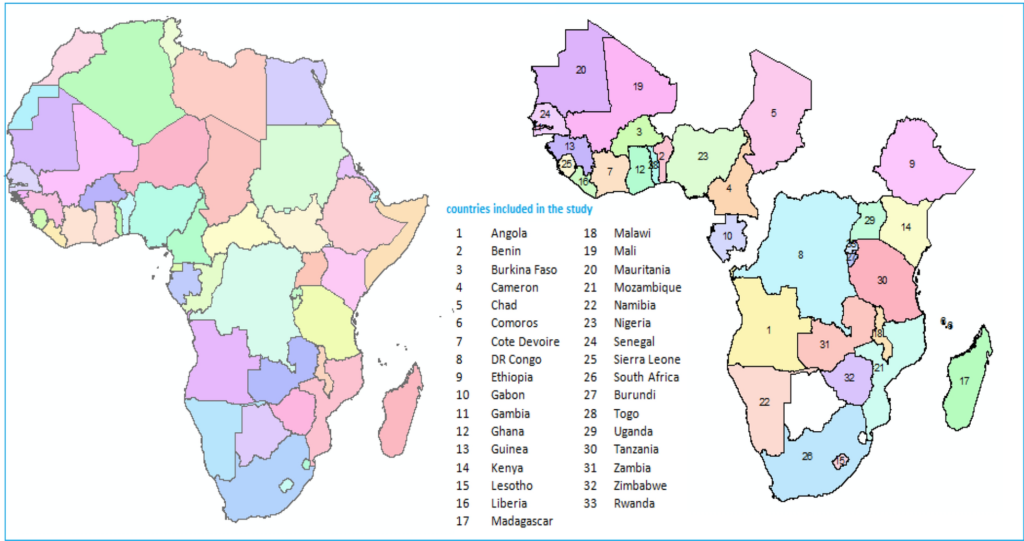

The pooled prevalence of adequate ANC service utilization in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA) was 55% (95% CI: 54–56). It was higher than South Asian countries (46.64%) [18] and East African countries (52.44%) [19]. These disparities could be attributed to the presence of health system infrastructure, sample size, policy variations against maternal health care services, survey year, variability in awareness of maternal health care services, and socio-cultural differences between countries. The results of the random effects analysis showed that variables at the community and individual levels were responsible for approximately 62.60% of the variation in the use of adequate ANC services. Similar finding in sSA countries [38] and South Asian countries [18] revealed that community and individual-level factors contributed to a large difference in the utilization of adequate ANC services across communities. This is because women who reside in the same communities are more likely to have similar results than women who live in different communities because they share similar characteristics and have access to the same maternal health care.

The two-level logistic regression model revealed that woman’s education, woman’s occupation, age, marital status, husband’s education, husband’s occupation, sex of household head, media exposure, distance to health facilities, getting the money needed for treatment, residence, age at first birth, contraceptive use, women’s decision-making capacity, pregnancy wanted, birth order, wealth index, and region were significantly associated with the use of adequate ANC service utilization.

The study found that maternal and husband education was a strong predictor of ANC visit utilization. The likelihood of receiving adequate ANC increases as the women’s and husband’s education levels rise. This is in line with the studies carried out in South Asian countries [18], Debre Tabor Town, northwest Ethiopia [39], South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia [14], Ethiopia [40], Northern Ghana [15], Nepal [41]and sub-Saharan Africa countries [38]. Their possible justification could be that education improves maternal healthcare service utilization and increases knowledge of specific issues. Furthermore, empowering women through education, household wealth, and decision-making improves maternal healthcare service utilization.

Women aged 35 to 49 years were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than women aged 15 to 24 years. This finding is in line with studies done in Debre Tabor Town, northwest Ethiopia [39], rural Ghana [42], Indonesia [43] Nepal [41], and the Philippines and Indonesia [44]. The possible reason for this is that older women in the higher age’s have more experienced knowledge about the importance of maternal health due to having more exposure to health care services information during pregnancy. The findings also showed that the odds of receiving adequate ANC increase as women’s age at first birth increases. This finding was in agreement with a study done in South Asian countries [18]. Working women were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than housewives women. This finding is similar to a study in Nepal [41], Bangladesh [45], Indonesia [43] and sub-Saharan Africa [38]. This could be because working women benefit from a pregnancy care health insurance system and share maternal health care knowledge with coworkers. Female household heads were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than their male counterparts. This finding was supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia [46]

Women who had autonomy on their own had a higher likelihood of receiving adequate ANC than women who had autonomy decided with their husbands. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Nepal [41], South Asian countries [18], and sub-Saharan Africa [38]. This could be because women’s autonomy in terms of maternal healthcare utilization allows them to make decisions about their healthcare. The study also showed that married women had a higher likelihood of receiving adequate ANC services than single (divorced/windowed) women. This result is consistent with studies conducted in rural Ghana [43]and Indonesia [43]. Compared to their unmarried counterparts, the married women’s planned and desirable pregnancies, societal acceptance and support of their pregnancy state, and the psychological and financial support they received from their husbands may all have contributed to the higher ANC service adequacy [16].

The wealth index was significantly associated with adequate use of ANC services. Women with a rich wealth index were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than poor women. This result is in line with studies done in Ethiopia [40], Northern Ghana [15], South Asian countries [18], and sub-Saharan African countries [38]. This could be because rich women have more access to healthcare and receive important information about adequate ANC services through mass media. Furthermore, this may be attributed to the indirect cost of ANC, such as transport costs when traveling to distant health facilities.

Women in urban areas had a higher chance of receiving adequate ANC services than rural women. This is consistent with the studies conducted in Ethiopia [40], South Asian countries [18], South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia [14], Northern Ghana [15], Indonesia [47], Nepal [41], and sub-Saharan Africa countries [38]. The possible explanation could be that urban women may have better education, and access to maternal health services, and are more aware of the importance of receiving adequate ANC services. The odds of adequate ANC visits were higher among women where distance to a health facility is a big problem compared to women whose distance to a health facility is not a big problem. This is supported by the previous studies conducted in Delta State, the Southern part of Nigeria [48], Indonesia [47], and sub-Saharan African countries [38].

Mass media exposure is associated with adequate ANC. Women who were not exposed to media received more adequate ANC services than women who were exposed to media. This finding is supported by a study done in Ethiopia [40], Delta State, Southern part of Nigeria [48], South Asian countries [18], South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia [14], Bangladesh [45], and sub-Saharan Africa countries [38]. This is because women who received messages about maternal health care services via radio, television, and newspapers were more likely to use ANC services.

Women with unwanted pregnancies were less likely to receive adequate ANC services than those with wanted pregnancies. This finding is in line with studies done in Debre Tabor Town, northwest Ethiopia [39], South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia [14], and sub-Saharan African countries [38]. This could be attributed to unplanned pregnancies and unwillingness to seek adequate ANC services. The lack of a pregnancy mindset, which is common in unplanned pregnancies, may have negatively impacted mothers’ use of ANC services. If the pregnancy is planned, women want to have a healthy pregnancy and may pay special attention to receiving adequate ANC service.

Women who used contraception were more likely to receive adequate ANC services than women who did not use contraception. This finding was in agreement with a study done in sSA countries [38]. Women with birth orders 2–4 and 5 and above had a lower chance of receiving adequate ANC services than women with first birth orders. A similar finding was also found in Ethiopia [49] and sub-Saharan African countries [38].

Geographic region was found to be significantly associated with adequate use of ANC services in sub-Saharan Africa. Women in Southern and Western sub-Saharan Africa were more likely to use ANC services than women in Central sub-Saharan Africa. This is in line with the studies carried out in sub-Saharan African countries [38]. This could be due to differences in the availability of medical facilities. Women from western sub-Saharan Africa, where the quality of health care services is better than in central sub-Saharan Africa, are more informed about maternal health care services as a result of economic and technological advances.

This article was originally published by a tropmedhealth.biomedcentral.com . Read the Original article here. .