The galaxies after the Andromeda galaxy (M31) and the Milky Way.

Star Formation in M33

M33 is known to be a hotbed of starbirth, forming stars at a rate 10 times higher than the average of its neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy. Interestingly, M33’s neat, organized spiral arms indicate little interaction with other galaxies, so its rapid starbirth is not fueled by galactic collision, as in many other galaxies. The galaxy contains plenty of dust and gas for churning out stars, and numerous ionized hydrogen clouds, also called H-II regions, that give rise to tremendous star formation. Researchers have offered evidence that high-mass stars are forming in collisions between massive molecular clouds within M33.

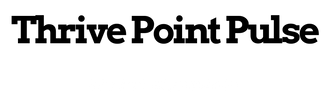

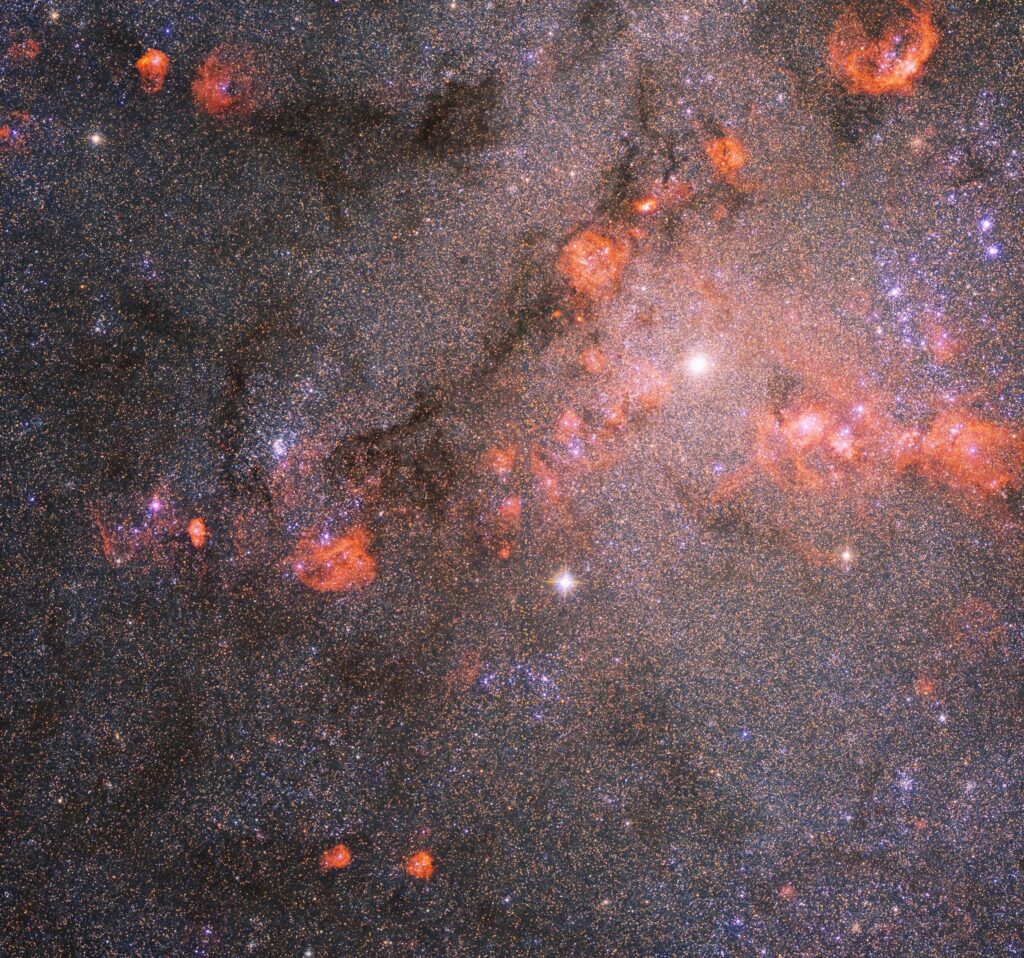

This image captures reddish clouds of ionized hydrogen interspersed with dark lanes of dust. The apparent graininess of the image is actually swarms of countless stars. M33 is one of less than 100 galaxies close enough for telescopes like Hubble to resolve individual stars, as evident here.

Unique Structural Features of M33

M33 is known to lack a central bulge, and there is no evidence of a supermassive black hole at its core ― strange since most spirals have a central bulge made up of densely concentrated stars and most large galaxies have supermassive black holes at their centers. Galaxies with this type of structure are called “pure disk galaxies,” and studies suggest they make up around 15-18 percent of galaxies in the universe.

M33 may lose its streamlined appearance and undisturbed status in a dramatic fashion ― it’s on a possible collision course with both the Andromeda galaxy and the Milky Way. This image was taken as part of a survey of M33 in an effort to help refine theories about such topics as the physics of the interstellar medium, star-formation processes, and stellar evolution.

This article was originally published by a scitechdaily.com . Read the Original article here. .